Mr. Martin Griffiths, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, OCHA, called for the humanitarian response to be “local as possible, as international as necessary.” This came in an exclusive interview with Qatar Charity’s (QC) ‘Ghiras magazine, in which he indicated the growing importance of localizing humanitarian action.

He also praised Qatar Charity’s operating model that allows it to be close to local partners on the ground, noting that Qatar Charity funds local organizations as directly as possible.

Griffiths also casted light on the most important criteria and the mechanism to achieve the localization, and on the most significant challenges facing the localization agenda, touching on how to enable local humanitarian organizations to respond to crises more quickly and more effectively.

Below is the complete interview

In your opinion, as Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, OCHA, what is the importance of localizing humanitarian action? Why is there a demand for this globally?

Mr. Martin Griffiths: Humanitarian response should be “local as possible, as international as necessary.” That thinking emerged strongly from the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit (WHS).

However, since then, only about 5 per cent of international funding has gone to local or national Governments, charities, or other non-profit organizations.

There has been a long-standing demand from local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for equal footing in humanitarian response. The NGOs say they are often overlooked and underfunded, and international aid organizations, including the United Nations, should allow them the space to grow and take on more responsibility.

There are several reasons for the growing importance of localizing humanitarian action.

First, local NGOs are on the ground before, during and after a crisis. They are first responders but also providers of long-term support. They know and understand the local context of providing support far better than international responders do. Being part of the community, they often have extensive local knowledge, which helps them identify the most vulnerable groups that need assistance.

Second, local NGOs also have the experience of dealing with past emergencies, which makes them extremely effective in a humanitarian response. For example, at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, several NGOs used and adapted their experience in dealing with cholera, Ebola and Zika to prepare communities to face a pandemic.

Third, at a time when international humanitarian support is stretched more thinly than ever in low-income countries, local NGOs are playing a critical role in responding to people in need. The pandemic highlighted the relevance of local actors, who were able to access hard-to-reach areas more swiftly, efficiently, and easily than their international counterparts.

Last, but not least, there have been calls to end the domination of organizations from the global North and to empower local NGOs, especially those headed by women, to lead and influence humanitarian action.

What are the most important criteria to achieve localization?

Mr. Martin Griffiths: Localization requires a culture shift towards a system that puts affected communities and their representatives at the centre of crisis response, making way for their influence and decision-making. The need to promote greater agency of local and national organizations and entities must be rooted in each response to a humanitarian crisis.

Local and national actors’ involvement in a response should go beyond a fairer share of funding and opportunities to deliver projects – although that is a good beginning. They should also lead and be part of the process that designs, delivers, and monitors the response. Decisions related to humanitarian action in a community or country should be validated with communities affected by the crisis. We must do everything we can to make their contributions more visible.

What are the most significant challenges facing the localization agenda?

Mr. Martin Griffiths: First is the issue of leadership and ensuring that humanitarian response, wherever possible, is locally led or co-led while the humanitarian principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence are respected.

International organizations have dominated the last five decades of humanitarian action. In some conflict situations, international organizations may be able to advocate for access more successfully, and international skills and experience may be particularly useful in cases such as trauma surgery or camp management. However, the culture of sharing power and decision-making with local organizations still does not come naturally in this sector.

Second is the issue of meaningful participation and equity, or in other words, not only do local actors get a seat at the table but they are truly welcomed as equal partners, given adequate visibility and able to influence decision-making processes.

This also means guaranteeing that they have the adequate space and support to express their opinions. This would mean, for example, providing translation and interpretation so that language does not present a barrier.

We also need to support locally led coordination platforms and local leadership and ensure greater gender balance.

International humanitarian actors need to acknowledge this new role as enablers of local and national leadership. It also means that the existing humanitarian architecture must include local and national actors as equal partners. None of this will be easy.

When was the localization of humanitarian work called for? Is there a timespan specified to achieve this? What is/will be the mechanism to move forward in this regard?

Mr. Martin Griffiths: The 2016 WHS brought significant attention to localization. Several changes were proposed in how donors and aid organizations achieve localization, and these proposals are known as the Grand Bargain – an agreement made at the WHS between donors and aid organizations that aims to get more resources into the hands of people in need.

To achieve this goal, the Grand Bargain set up various measures including a call for investment in local and national responders to improve their capacity; a “localization” marker to measure direct and indirect funding to local and national responders; and providing 25 per cent of funding directly to local responders by 2021. This 25 per cent target changed in 2021’s Grand Bargain 2.0 and was reflected as an “increase” and not as an absolute number.

Commitments were also made to ensure greater integration of local and national actors in coordination efforts. The Grand Bargain, led by the Eminent Person, Jan Egeland, monitors progress on these specific targets.

The initial timespan for meeting the Grand Bargain commitments was from 2016 to 2021.

The Grand Bargain 2.0. runs from 2022 to 2023.

The overall progress on localization is monitored by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee. This is a forum for coordination, policy development and decision-making related to humanitarian assistance provided by the UN and international NGOs. A combination of all these efforts will help us move the needle on some of these issues.

Is there any progress in localizing humanitarian action by UN bodies like OCHA and international organizations, according to your follow-up?

Mr. Martin Griffiths: I am proud to say that OCHA has made progress on the commitments we made at the WHS in 2016.

For example, the amount of funding that we allocate through Country-Based Pooled Funds, which OCHA manages, to local NGOs has steadily risen from 22.8 per cent in 2016 to 34 per cent in 2021.

But there is much more that needs to be done and improved, including around the quality of funding that goes to local responders. The Financial Tracking Service, which OCHA runs to track funding flows to humanitarian action globally, shows a dismal statistic: only 5 per cent of global funding for humanitarian efforts has gone to local and national entities since 2016. This must change. We also must have more local organizations leading and co-leading coordination structures.

In your opinion, to what extent does this localization contribute to developing the capacities of local humanitarian organizations to enable them to respond to crises more quickly and more effectively?

Mr. Martin Griffiths: These two issues are connected. True localization and effective response can only come about when we not only invest in and empower local partners to lead and respond quickly, but when we also support their capacity to develop. And developing capacities is not just about providing funding; it is also about ensuring investment in training, mentoring and other development opportunities for local organizations and leaders.

How do you see Qatar Charity’s performance in localizing humanitarian work, as one of the international organizations attaching significant attention to this matter?

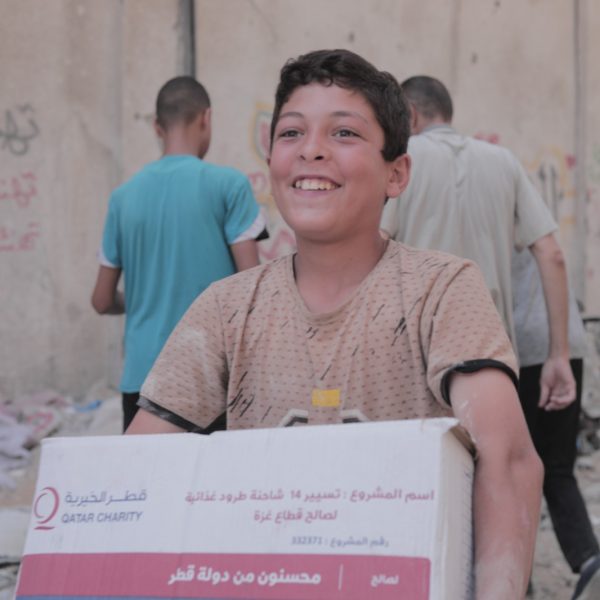

Qatar Charity’s operating model allows it to be close to local partners on the ground. It is also commendable that Qatar Charity funds local organizations as directly as possible. Local NGOs have been calling for this for a long time. This also aligns with the global humanitarian community’s objective.

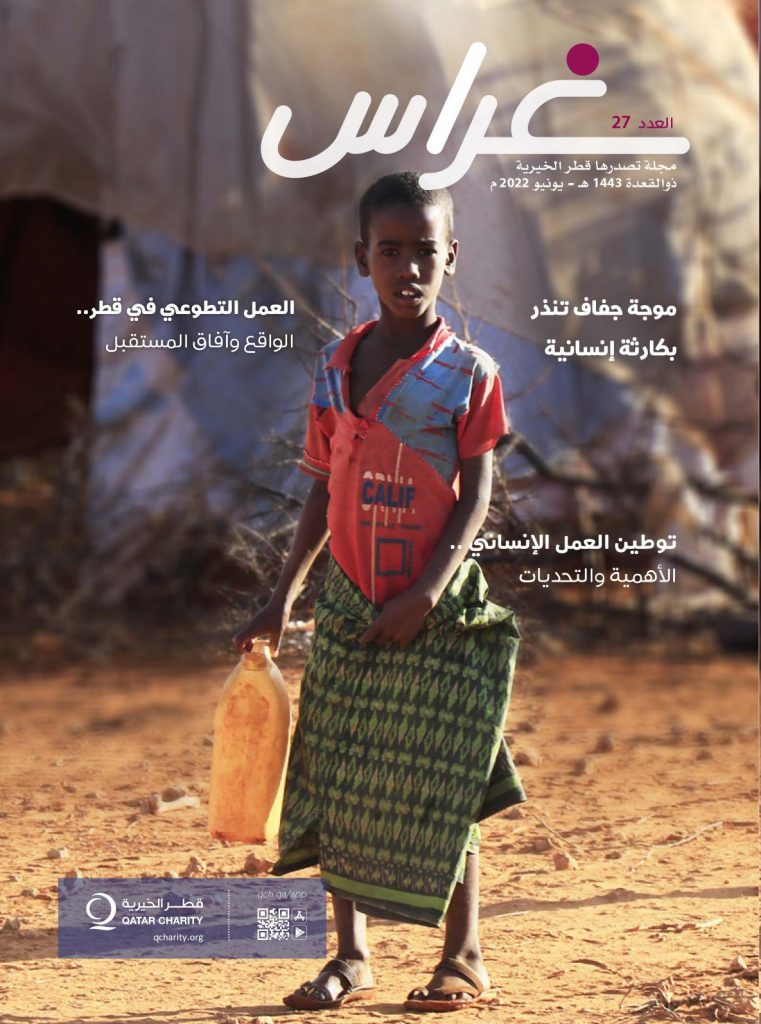

The article is published in the 27th issue of Ghiras magazine.

Download your copy of the magazine now or check out other articles.